Charting the life and influence of a Sāmoan independence giant

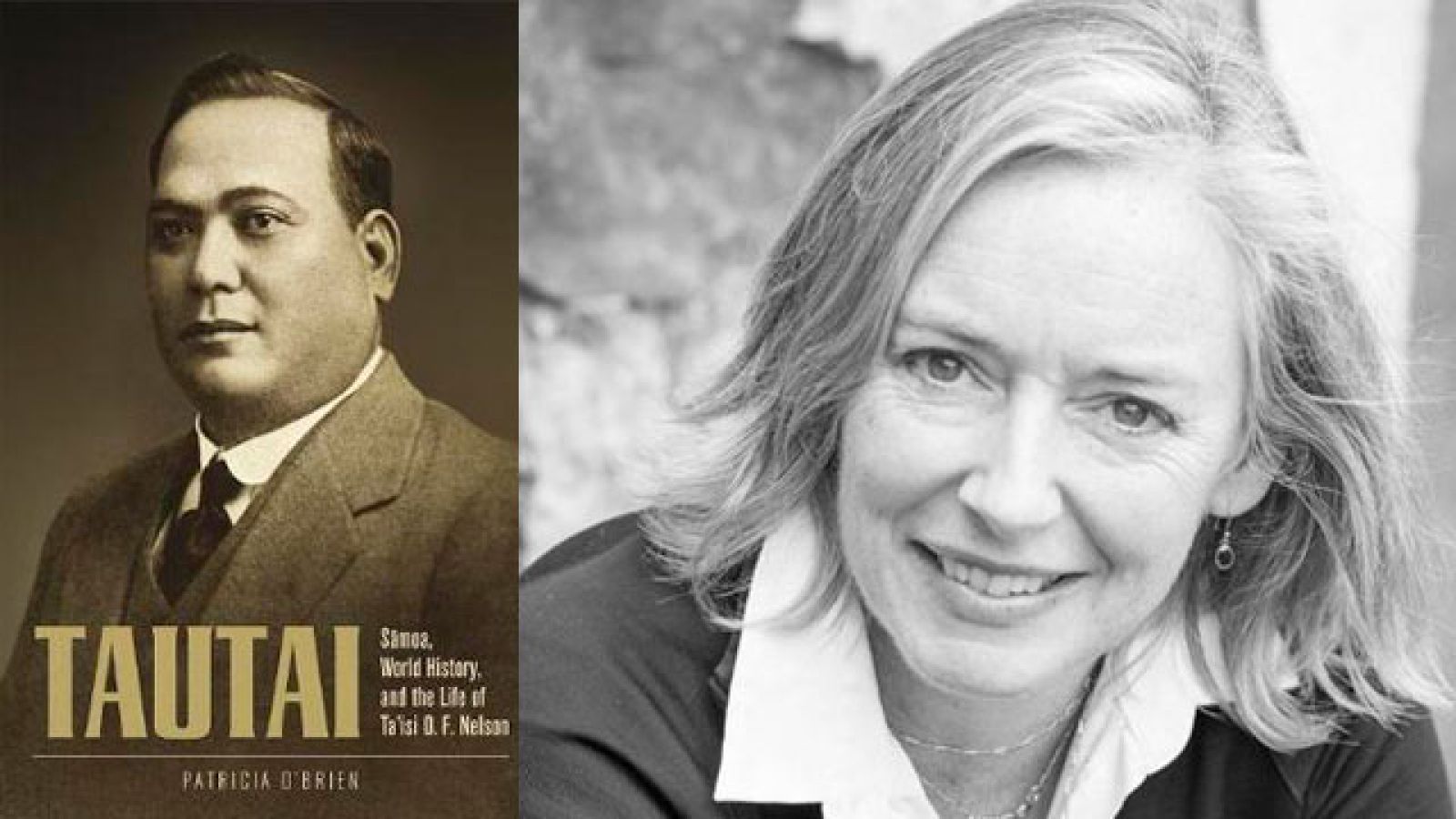

Research for Dr O'Brien's book, Tautai: Sāmoa, World History and the Life of Ta'isi O. F. Nelson, involved deep archival research including sources that had not been used previously.

A new book explores the little-known Ta'isi Nelson, leader of Sāmoa’s independence movement, and how his efforts inspired other non-violent struggles around the world.

Dr Patricia O’Brien’s Tautai: Sāmoa, World History and the Life of Ta'isi O. F. Nelson (University of Hawaii) has received wide acclaim across the South Pacific since it was published earlier this year.

“The book's reception by the Sāmoan community has been extraordinary in so many ways,” the ANU School of History-based ARC Future Fellow says.

“When you write a book you have modest hopes for it, but to have an immediate embrace by Sāmoan leaders and scholars, as well as a wide cross section of the community from school children to elders, has exceeded my wildest expectations.”

Respected figures have launched the book including Sāmoan Prime Minister Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi in Apia and former New Zealand Prime Minister, Helen Clark, in Auckland. Australian Senator Concetta Fierravanti-Wells, Minister for International Development and the Pacific, launched it in Sydney.

“On behalf of the Australian Government, I am pleased that we were able to support you through an Australian Research Council Grant, which you received in 2013,” Senator Fierravanti-Wells said.

“Dr O'Brien has shown us that, although Ta'isi did not live to see it, we live in the world that I hope he wanted.”

In the following Q and A, Dr O’Brien talks about working with Mr Nelson’s family, her writing methods, and advice to young historians.

From where did the idea to research and write Tautai: Sāmoa, World History and the Life of Ta'isi O. F. Nelson originate?

In 2012 I began a research project at Victoria University of Wellington on New Zealand’s rule of Sāmoa when it was a League of Nations mandate. It was when I was reading files in Archives NZ on this and kept coming across references to a ‘Mr Nelson’ that I became intrigued by this man.

A librarian directed me to some of his letters, but before I could read them I needed permission from his family, headed by Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Ta’isi Efi. With the family’s blessing, Ta’isi quickly became my focus as he had not been the subject of a dedicated study before and so clearly deserved to be drawn out from history’s shadows.

How did you approach the research?

The research for this book has involved deep archival research including sources that had not been used previously. As well as this archival work this book also involved relationship research, that is. working closely with many Sāmoans who were both family members and not, in order to piece together this history and to keep the Sāmoaness of the story prominent and conveyed in a way that rang true for Sāmoan people, but was also accessible for those with little previous knowledge of that nation's history. (There are more details about this approach in the acknowledgements and on p.369-370 of the book).

You say you don’t speak Sāmoan. How did you build a picture for the world you were describing?

I had not been to Sāmoa before working on the book, but have been there many times since 2012. Also I worked closely with the family and had access to Ta'isi's personal papers for the first time housed at his home of Tuaefu so I was able to see many things from Ta'isi's view points having spent a lot of time at his Apia home. Also I have traveled to places related to his life, like his home village of Safune. I don't speak Sāmoan (yet) but the many Sāmoans I have worked with have been instrumental in advising me on cultural details, as I outlined in the acknowledgements. I have worked closely with many Sāmoans and been immersed in Sāmoa and Sāmoan history so my ties are strong and complex.

I have drawn on many sources to picture the world I was writing about. Contemporary newspapers and photographic evidence were also very useful for this.

What do you hope people will learn from your book, about Ta’isi, or struggles for independence?

I hope that many more people will become not only literate in Sāmoan history but be able to rethink world history in the Sāmoa-centric way I present it. I hope that many more people will be able to recognise the contributions Ta'isi made to global struggles for independence and the way he went about his campaign, especially his adherence to non-violent political action and the way this connected to Maori struggles against British rule in preceding decades. The book also aims to detonate abiding racial stereotypes by offering a deep and detailed examination of a global political figure from the Pacific.

It’s great to see such coverage in Sāmoan media and large audiences for your book. What does that response mean to you as an historian and writer?

The book's reception by the Sāmoan community has been extraordinary in so many ways. When you write a book you have modest hopes for it but to have an immediate embrace by Sāmoan leaders and scholars, as well as a wide cross section of the community from school children to elders has exceeded my wildest expectations. I knew from previous papers I've given to Sāmoan audiences that there was a lot of curiosity and interest in the work I was doing. But the recent overwhelming embrace of Ta'isi's story shows it has struck a deep chord and has opened up this vital national story that was buried.

I have had so much generous feedback and it’s very clear that all the exacting work it took to write the book has already been rewarded many times over. I would also like to give credit to Sāmoan Prime Minister Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi, who I had not met until the recent launches. He said when launching Tautai that 'every Sāmoan should read this book'. This is possibly the only instance of a contemporary political leader urging constituents to read a scholarly historical work. This sends a powerful message.

Do you have any advice for current or potential students of history?

Like many people who love history and work in this field, I have been deeply appalled by recent attacks on scholarly practices and the dumbing down of historical studies in so many ways. I feared that what historians do was passé and no one was that interested any more (except those dreaded elites) in deep research and challenging stories. But my recent experience has restored my faith in the power of a book to really impact and influence people.

The celebration of Tautai, a scholarly book, by the Sāmoan community has been phenomenal. So my message to young historians is that if they are in direct communication with broad audiences, and you are telling engaging stories your work too can have deep meaning and relevance.

The study of history is vital and don't be discouraged by all the noise – be a tusitala, a writer, reporter and teller of tales.